In the remote fringe of Santa Cruz County, buttressed between high mountains and closer geographically to Santa Clara and San Benito counties as it is to Watsonville, the small community of Chittenden sits beside Soda Lake. Of all the railroad stops in the Santa Cruz County, this was the most isolated for it is the only stop of the mainline Coast Division of the Southern Pacific Railroad in Santa Cruz County. It also was the first stop in the county.

|

| Map of Rancho Salsipuedes, 1853. (UCSC Special Collections) |

Nathaniel W. Chittenden unintentionally leant his name to the station when he settled in what became known as Chittenden Pass around 1870. He had been until that time a lawyer from San Francisco. When he moved to Santa Cruz County, he purchased the eastern corner of Rancho Salsipuedes. The rancho had a long and disputed history, with its origins in a possible land grant to Mariano Castro in 1807, making it one of the few Spanish, rather than Mexican, land grants in the county. It was the second largest rancho in the county, as well, measuring 25,800 acres. Because of its large size and its disputed status, it was one of the first ranchos that was divided up following the American annexation of California. Its last Mexican owner was Manuel Jimeno Casarín. The soil of the rancho as a whole, but especially within the pass between the mountains, is highly fertile and the alkaline Soda Lake, the only such lake in the county, was a source for mineral collection. The road that passed through the pass became a county road in 1894 and it remains one of the primary means of passing between Santa Cruz and Santa Clara counties even today. Chittenden died in Watsonville in 1885, after which his lands were divided between his relatives. Idea H., Clara, and Talman Chittenden were his chief beneficiaries.

|

| The Chittenden community center, showing a small general store, c. 1900. (Santa Cruz Public Libraries) |

|

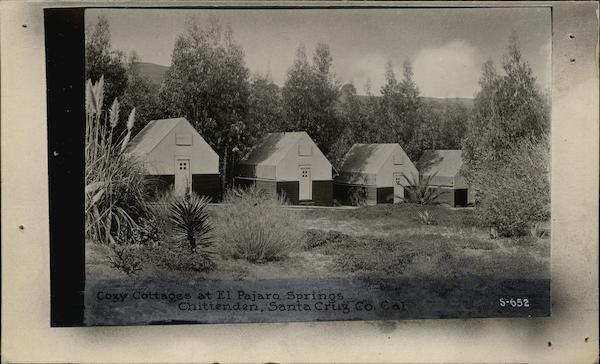

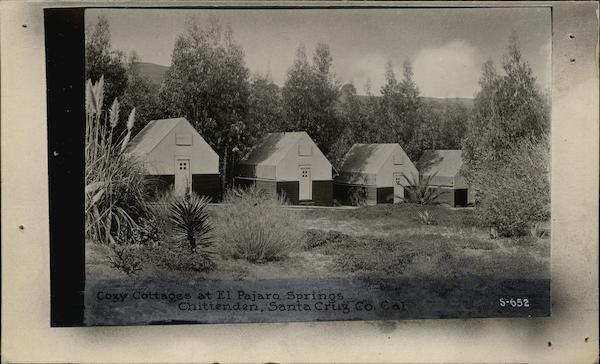

| El Pajaro Springs postcard, c. 1910. (CardCow.com) |

Chittenden as a settlement was never impressive—numbering fewer than 80 residents in 1893. The small community that lived in the gap still managed to establish a post office in April 1893 and kept it running for many years. The railroad station was probably established around the same time under the name "Chittenden's", later dropping the "s". In those early years, one of the primary draws of the region was Chittenden Springs, which was established beside a sulphur hot spring located in the gap. In 1906, the Chittendens sold the spring to A.F. Martel who renamed it El Pajaro Springs, a reference to the Pajaro River that still passes through the pass. In 1918, it was sold again to the St. Francis Hospital of San Francisco and it became St. Francis Springs. The resort was beside Soda Lake.

|

1906 San Francisco Earthquake damage at Chittenden.

(Granite Rock Company) |

The railroad stop at Chittenden was primarily used for freight. Passengers could use the facility as a flag-stop, but no agency office was available there to purchase tickets. No passenger shelter appears to have been built initially. A siding (or pair of sidings) at Chittenden ran along the north side of the tracks, between where the tracks are today and State Route 129, branching off near the first major driveway over the tracks and merging just before where the highway crosses under the tracks. A spur may have run to Soda Lake as there is some topographical evidence of such. If so, this route would be identical to the dirt road that now leads to the lake. Mining operations in the hills continued into at least the 1910s and used the sidings to store waiting cars. In addition, there were vast clay deposits along the banks of the Pajaro River and along Pescadero Creek above Chittenden, which were mined as well. By the early 1900s, Granite Rock Company also used the sidings to store firewood-filled boxcars that were used in their kilns at Logan.

|

| Chittenden's small post office building with a man posing out front, 1900. (Santa Cruz Public Libraries) |

|

Boxcars damaged by the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, at Chittenden.

(Granite Rock Company) |

Around the time that Chittenden as a community was fading, the railroad operations out of the station received an unexpected boost. The San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 certainly helped in that it increased demand for all building supplies, such as the mineral, clay, and limestone deposits in and around the San Benito and San Juan valleys. For at least a year already, the Ocean Shore Electric Railroad was intending to pass through Chittenden Gap to connect to a proposed mainline route in the San Joaquin Valley. But a group of trigger-happy investors decided that a route to San Juan Bautista would help progress things a bit faster. When negotiations with the Southern Pacific Railroad failed, the group relocated their planned northern terminus from Betabel to Chittenden. The San Juan Pacific Railway was incorporated on May 4, 1907, and construction began almost at once out of Chittenden with the route completed August 30.

Initial plans were to build the railroad's right of way directly under the Southern Pacific tracks with a yard and station built on their northern side. But this goal was for another day. Initially, they crammed in a two-track yard on the south side, between the Southern Pacific tracks and the Pajaro River embankment. A small freight platform and passenger shelter were erected beside the tracks. The tracks were connected to a Southern Pacific siding on either side allowing entry and exit in either direction along the line. Curiously, the railroad had no wye at either end, suggesting there was possibly a turntable somewhere along the line (and potentially at both ends). No evidence for a turnable, however, has been found. The northern water towers were kept at Chittenden just before the Pajaro River bridge crossing to the east.

|

| San Juan Pacific passenger shelter and freight platform at Chittenden, 1908. (Santa Cruz Public Libraries) |

For the remainder of its life, Chittenden Station was more a transfer point between the San Juan Pacific (later California Central) and the Southern Pacific. Until early 1909, passengers transferred here for rides down to San Juan Bautista on the "Old Mission Route" and there was occasional bustle at the stop, but that all collapsed pretty quickly when financial difficulties ended passenger service permanently along the line. When the California Central took over in 1912, it did not resume passenger service. From 1916 to 1929, cars from the Old Mission Cement Company plant south of San Juan Bautista would transfer to passing Southern Pacific trains for delivery to various customers. Meanwhile, empties cars or cars with cement supplies would return to the sidings awaiting shuttling back to the plant. This was what kept Chittenden alive for so long. The town's post office had closed June 15, 1923, and the town had disappeared in the meantime. All that was left was a tiny freight transfer yard.

In 1930, the cement plants switched to using trucks exclusively for transport and the California Central essentially ceased to exist. The route rusted and Chittenden became a silent unused flag stop. In 1937, the last train passed up the Old Mission Route, depositing its remaining rolling stock on the Southern Pacific line for sale out of county. The route was dismantled and Chittenden's purpose to the railroad was officially ended. During World War II, Southern Pacific quietly closed Chittenden station on April 7, 1942, and it ceased to be a flag stop. It remained as a potential freight stop into the mid-1950s but was likely never used during this time. El Pajaro Springs is surprisingly still listed on Google Maps as a site to the west of Soda Lake, but no structures appear in the area. The area is classified as unincorporated Santa Cruz County land and, with the exception of a florist, there are no commercial structures remaining in Chittenden today.

Official Railroad Information:

On the Southern Pacific Coast Division, Chittenden Station was 91.9 miles from San Francisco via the mainline track through San José, and it was 28.6 miles from Santa Cruz. It included 123 car lengths of siding and spur space, which may or may not have included a special track to Soda Lake, where a mining firm was always attending to the lake's minerals.

For the San Juan Pacific, Chittenden was mile marker 10.0 along their lines, which set 0.0 miles at San Juan Junction. In the first year of operation, passenger service ran both directions three times per day, but that ended in early 1909. Fewer records are available for the California Central Railroad since it operated freight exclusively along roughly 8 miles of track. Chittenden's mile marker or its trackage capacity are unknown.

Geo-Coordinates & Access Rights:

36.900˚N, 121.601˚W

|

| 1917 USGS Map showing Chittenden area with original trackage. |

The site of Chittenden Station is accessible from Old Chittenden Road via State Route 129. The station site itself is unmarked but is near the Happy Boy Farms property on the eastern end of the road. The freight yard outline is discernible by the large loop that the road makes away from the tracks before paralleling them. The original site of the San Juan Pacific depot is not known with certainty but at the top of the embankment above the Pajaro River in what is undoubtedly today private land.

Trespassing is not advised. Except for the one remaining

active Union Pacific track in the area, nothing else remains of Chittenden Station or the historic town except for a few Victorian-era scattered homes.

Citations:

- Clark, Donald. Santa Cruz County Place Names: A Geographical Dictionary. Scotts Valley, CA: Kestrel Press, 2003.

- Hamman, Rick. California Central Coast Railways. Santa Cruz, CA: Otter B Books, 2002.